Tumor Boards are among the most exciting and popular sessions at the WCIO Annual Scientific Meeting. During the WCIO 2012 HC C tumor board, program chair Riad Salem, MD MBA presented a series of increasingly complex cases to an international multidisciplinary panel of experts. The final case was a large infiltrative HCC invading the main portal vein, with a markedly elevated AFP, but preserved liver function (Childs A) and performance status (ECOG 0). The ensuing discussion was lively and enlightening. A hepatologist said he would put the patient on sorafenib as first-line therapy. Some of the interventional oncologists said they would do radioembolization. What went unrecognized in the discussion is that all the panelists were wrong.

C tumor board, program chair Riad Salem, MD MBA presented a series of increasingly complex cases to an international multidisciplinary panel of experts. The final case was a large infiltrative HCC invading the main portal vein, with a markedly elevated AFP, but preserved liver function (Childs A) and performance status (ECOG 0). The ensuing discussion was lively and enlightening. A hepatologist said he would put the patient on sorafenib as first-line therapy. Some of the interventional oncologists said they would do radioembolization. What went unrecognized in the discussion is that all the panelists were wrong.

This patient is likely to die within a few months, and almost certainly within the year. Treatment might extend his survival; a good rule of thumb is that liver-directed therapy will on average double the patient’s prognosis. Even with treatment, this patient will most likely die of liver cancer within the year.

So why did I say that the tumor board panelists were wrong? In the face of almost certain death from cancer, patients can only make informed choices about therapy if they understand the risks and benefits relative to no therapy. It is the interventional oncologist’s responsibility to frame the big picture, starting with the expected trajectory of the illness if the patient chooses to do nothing. The first therapy to discuss is 6PFP: Six-Pack and a Fishing Pole. For most new patients I see, no one has had this conversation with the family. Patients are almost always too afraid to ask, but they want to know and will thank you for it.

Once the patient and family have a grip on the prognosis without therapy, they can make informed decisions about possible interventions. We do not “put patients on sorafenib” or “do radioembolization”; we offer therapies which have well-defined toxicities and risks, with the hope of delaying the inevitable with acceptable impact on quality of life. Keep in mind that most patients even with advanced disease are asymptomatic and leading a normal life. Any treatment will have a negative impact on their quality of life at least temporarily, perhaps significantly if they suffer a complication, and will not alter the ultimate outcome. Options should be explained balancing the risks and toxicitIes against the probability of benefit. It is important to preserve the patient’s autonomy in deciding how he wants to spend the last several months of life, including the choice to do nothing.

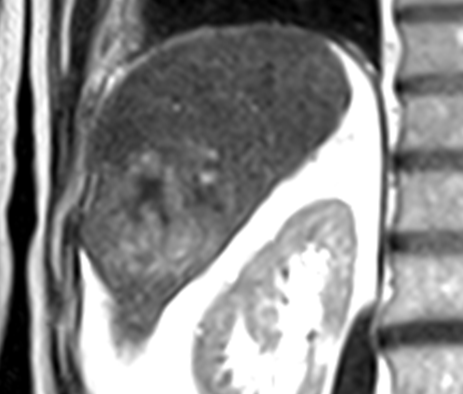

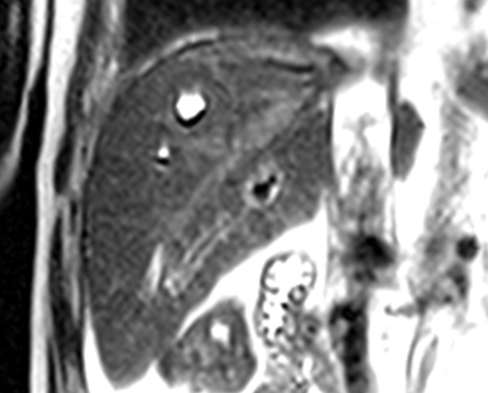

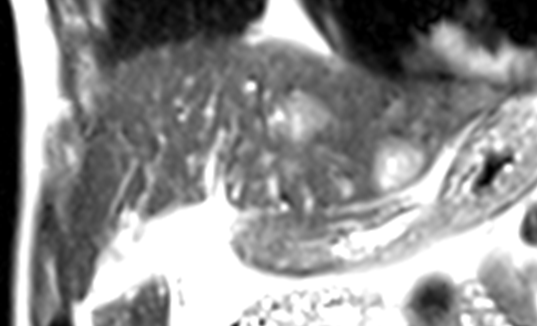

That being said, it is also important to preserve hope. One critical prognostic factor not known at the time of the initial consultation is response to therapy. Even a patient with multiple poor prognostic factors at presentation can move way out the expected survival curve if he has a dramatic response to treatment. The following patient of mine is similar to the one presented by Dr. Salem. An 8cm right lobe infiltrative HCC invades the hepatic vein up to the IVC, with satellite tumors in the left lobe. [images 1-3]

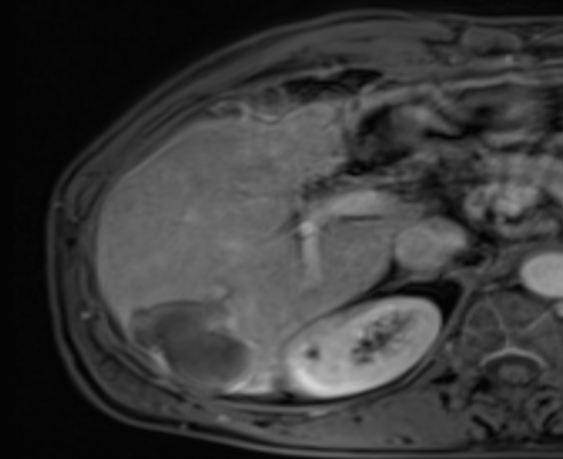

His AFP was 35,000, Childs class A, performance status ECOG zero. Under the Barcelona system he would be c lassified as stage C, and triaged to die on sorafenib within months. Instead he underwent chemoembolization, with complete tumor response by necrosis criteria and a normal AFP level two years later. [image 4]

lassified as stage C, and triaged to die on sorafenib within months. Instead he underwent chemoembolization, with complete tumor response by necrosis criteria and a normal AFP level two years later. [image 4]

Caring for patients with fatal cancers requires compassion, empathy, and respect. It is all too easy to let enthusiasm for minimally-invasive, image-guided therapies dominate the discussion. Every consultation should start with “You can choose to do nothing. If you decide to do nothing, this is what you can expect....” Don’t forget about 6PFP.